I

New York Times Best-Selling Author of These Truths

I

I

I

J

LL

LEPORE

I

I F T H E N

I

How the Simulmatics Corporation

I

Invented the Future

September 15, 2020

“A person can’t help but feel inspired by the riveting intelligence and joyful curiosity of Jill Lepore. Knowing that there is a mind like hers in the world is a hope-inducing thing.” —George Saunders

A revelatory account of the Cold War origins of the data-mad, algorithmic twenty-first century, from the author of the international bestseller These Truths: A History of the United States.

P R E O R D E R

“Data science, Jill Lepore reminds us in this brilliant book, has a past, and she tells it through the engrossing story of Simulmatics, the tiny, long-forgotten company that helped invent our data-obsessed world, in which prediction is seemingly the only knowledge that matters. A captivating, deeply incisive work.” —Fredrik Logevall, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam

“In this page-turning, eye-opening history, Jill Lepore reveals the Cold War roots of the tech-saturated present, in a thrilling tale that moves from the campaigns of Eisenhower and Kennedy to ivied think tanks, Madison Avenue ad firms, and the hamlets of Vietnam. Told with verve, grace, and humanity, If Then is an essential, sobering story for understanding our times.” —Margaret O’Mara, author of The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

“Everything Jill Lepore writes is distinguished by intelligence, eloquence, and fresh insight. If Then is that, and even more: It’s absolutely fascinating, excavating a piece of little-known American corporate history that reveals a huge amount about the way we live today and the companies that define the modern era.” —Susan Orlean, author of The Library Book

“In another fast-paced narrative, Jill Lepore brilliantly uncovers the history of the Simulmatics Corporation, which launched the volatile mix of computing, politics, and personal behavior that now divides our nation, feeds on private information, and weakens the strength of our democratic institutions.” —Julian E. Zelizer, author of Burning Down the House: Newt Gingrich, the Fall of a Speaker, and the Rise of the New Republican Party

How It Worked

by Jill Lepore

Before FiveThirtyEight...

In the twenty-first century, campaigns and political consultants use Simulmatics-style simulations all the time, and so do news organizations like FiveThirtyEight. In 2020, the Washington Post launched an interactive election simulator. This stuff started in 1959, with the Simulmatics Corporation.

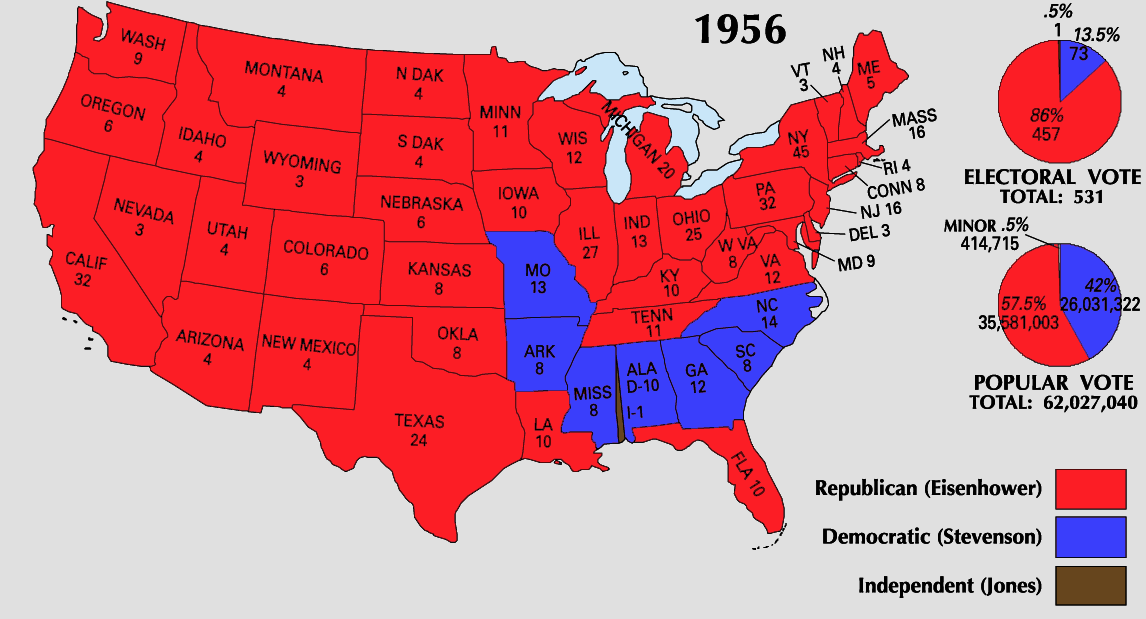

The first general-purpose computers became available in the 1950s, an era that also saw the development of a new computer language, FORTRAN, and a growing sophistication in the quantitative study of voting behavior. In 1956, the incumbent Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower ran against Democratic challenger Adlai E. Stevenson. That May, Eugene Burdick, a political scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, said he could predict a voter’s preference with a quiz of only twenty questions. He published his quiz in a popular Sunday newspaper supplement, alongside an article called “Science Thinks It Can Predict How You’ll Vote This Fall.” You can take that quiz here. You see these kinds of quizzes all the time in 2020: here’s one from the New York Times. What was different in 1956?

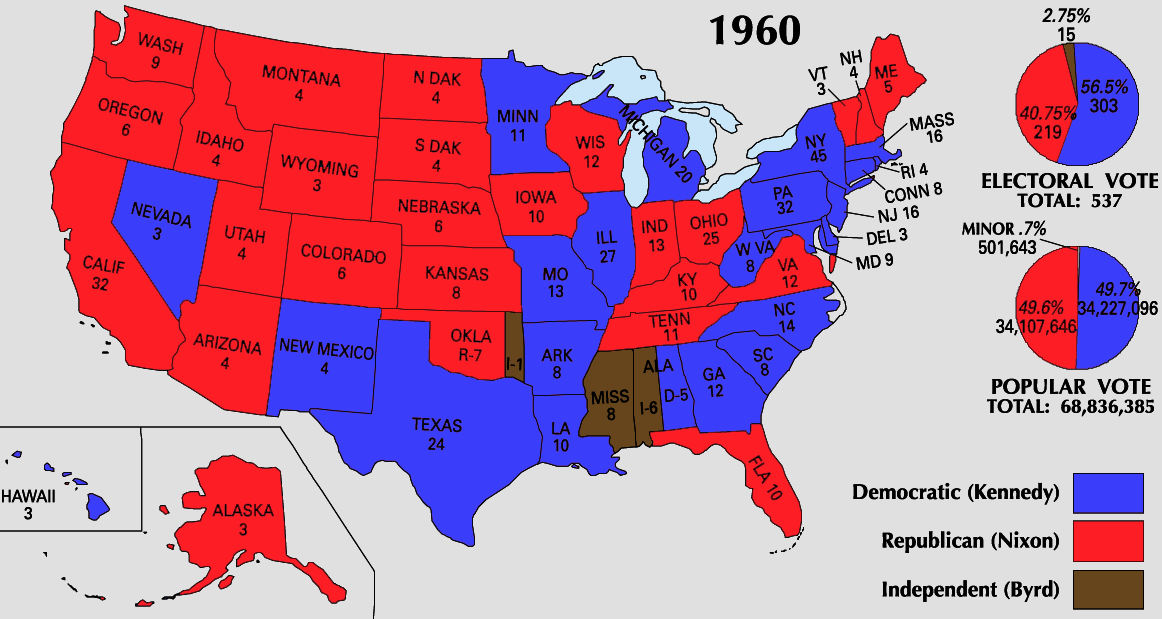

The future of the Democratic Party turned on the question of civil rights. To win back the White House, Simulmatics argued, the Democratic nominee needed to take a stronger position on civil rights. The company prepared its first report, "Negro Voters in Northern Cities", for the Democratic National Committee in May of 1960. After the Democratic National Convention that July, where John F. Kennedy won the nomination, Simulmatics presented his campaign with a formal proposal. Commissioned by the Kennedy campaign, Simulmatics prepared three more reports, including "Kennedy Before Labor Day." When Kennedy won, in one of the closest elections in American history, Simulmatics claimed credit for his victory. The electoral map looked very different than it had in 1956.

Before Cambridge Analytica...

Did the Kennedy campaign “cheat”? A lot of Americans thought so. “Did IBM Computer Draft Strategy Send Kennedy to White House?” was the headline of one newspaper story. The New York Herald Tribune reported that the People Machine, “a big, bulky monster called a ‘Simulmatics’” had been Kennedy’s “secret weapon.” The Kennedy campaign denied relying on Simulmatics, but plenty of commentators were worried about the consequences of treating voters like bits of data, to be sorted, segmented, played against one another, and manipulated by computer models.

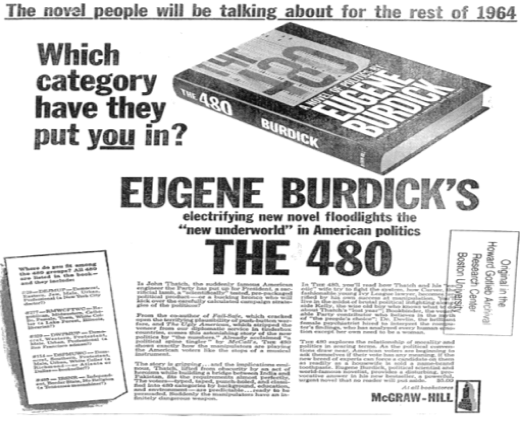

Eugene Burdick was particularly worried. In 1964, he published a dystopian political thriller called The 480, an indictment of Simulmatics.

Burdick described the scientists of the Simulmatics Corporation as constituting a new political underworld, posing a threat to democracy itself. He warned:

Was Burdick right? Did the Simulmatics Corporation alter

American politics as we know it?

The Original Simulator

Simulmatics went bankrupt in 1970 and most of the company’s records were destroyed but a collection of the original punch cards, along with computer printouts of the collated data, survives in Ithiel Pool’s papers at MIT. A team of researchers has salvaged the data, with the help of the Computer History Museum and the MIT Archives.

Coming soon: you’ll be able to try your hand at crafting a perfect political strategy for Kennedy in 1960, by playing with the data in a reconstructed 1960 People Machine.

Before Big Data, Machine Learning, and the

Algorithm-ing of Everything...

Eugene Burdick wasn’t an idle observer. During the Election of 1956, he worked with Madison Avenue ad man Edward L. Greenfield and MIT political scientist Ithiel de Sola Pool, providing political consulting to the Stevenson campaign. Stevenson lost. The only states he won were states that had been part of the Confederacy.

Three years later, in 1959, Greenfield and Pool founded the Simulmatics Corporation, a pioneering predictive analytics company, to help the Democratic nominee win in 1960. (They asked Burdick to join the company but he refused.) To build what they called a “People Machine”--really a series of programs, written in FORTRAN, for an IBM 704--Simulmatics scientists aggregated public opinion polls from 1952, 1954, 1956, and 1958. They collected punch cards from Gallup and Roper, processed them all, and re-tagged all the data.

The Simulmatics Project, as they called it, was, at the time, the largest social science research project ever conducted. “To handle such massive data required substantial innovations in analytical procedures,” they explained. They sorted voters into 480 possible “voter types, each voter type being defined by socio-economic characteristics.” Then they sorted the issues on which voters had been surveyed into 52 “issue clusters.” And then they ran their analyses.

“The new underworld is made up of innocent and well-intentioned people who work with slide rules and calculating machines and computers which can retain an almost infinite number of bits of information as well as sort, categorize, and reproduce this information at the press of a button. Most of these people are highly educated, many of them are Ph.D.s, and none that I have met have malignant political designs on the American public. They may, however, radically reconstruct the American political system, build a new politics, and even modify revered and venerable American institutions—facts of which they are blissfully innocent.”

Images: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library (National Archives, public domain)

Jill Lepore

Jill Lepore is the David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History at Harvard University. She is also a staff writer at The New Yorker. A prize-winning professor, she teaches classes in evidence, historical methods, humanistic inquiry, and American history. Much of her scholarship explores absences and asymmetries in the historical record, with a particular emphasis on the history and technology of evidence. As a wide-ranging and prolific essayist, Lepore writes about American history, law, literature, and politics. She is the host of the podcast The Last Archive, and author of many award-winning books, including This America: The Case for the Nation (2019; Liveright) and the international bestseller These Truths: A History of the United States (2018; W.W. Norton & Company).

© 2020 Liveright Publishing • A Division of W.W. Norton & Company • wwnorton.com